I have an up and coming TDAA Judges’ Clinic. One of the participants writes to me: “I don’t have a confidence that I can design an appropriate game for all three levels. I admit that don’t do very many gambles in any of my aspects of agility. I haven’t taught my dogs (or been taught myself) how to do them.”

She correctly assumes that experience is the best teacher. Inasmuch as I’ll be leading the judges’ clinic, I will endeavor to be the second best teacher. (The clinic and subsequent trial are in Lynnwood, Washington… October 9-12. Are you going to be there?)

A Few Quick Notes

Working a dog at a distance basically means that the dog has been taught his job and doesn’t require the handler to always be forward and always “dragging” the dog through every performance. The dog should be taught his job for every obstacle with no requirement that the handler be embedded in the context of the performance.

I’d be delighted to write a primer on the subject. That’s too big a job for this one blog. So the following is hardly comprehensive. I will write more on it and put it all together in the fullness of time.

The Handler’s Job

The handler’s job is to direct the dog. An important part of the distance riddle is how the handler provides direction. The easy answer to this is that the handler provides focus, verbalization and movement to frame the objective obstacle.

Focus is what the handler is looking at and pointing at. Note that pointing is not really a wagging finger. It is more defined by the set of the handler’s shoulders, hips and toes.

Verbalization is the verbal command or imperative annunciated by the handler to cue the dog to the objective obstacle.

Movement rightly belongs at the top of the list. The pressure of movement surely gives the dog his directional cues. The handlers movement tells the dog both where “we” are moving, but how quickly we intend to get there.

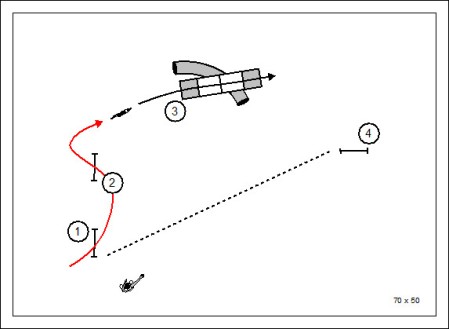

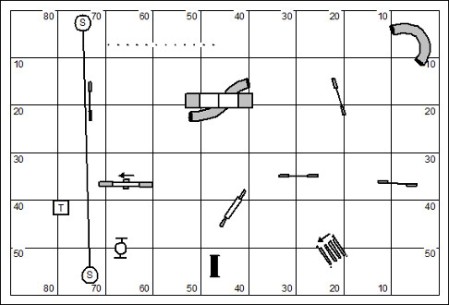

The Dead Away Send

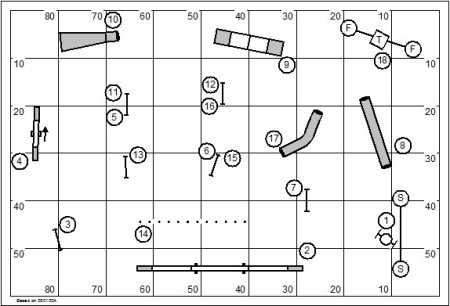

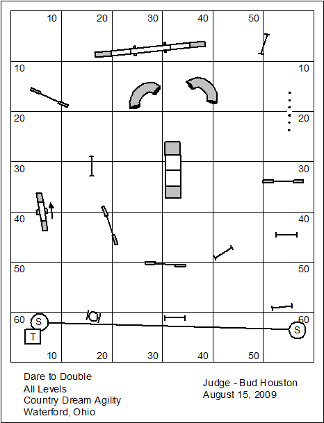

If it’s true that movement is the most fundamental cue to direct the dog, then we’d have to assume that sending the dog straight away (the “dead away” send) is the most difficult kind of distance challenge. In a gamblers’ class the judge will draw what’s called the “handler containment” line. The gamble/distance challenge is negated if the handler steps over that line.

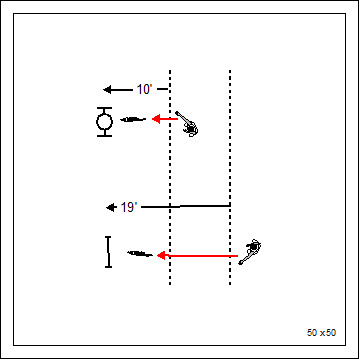

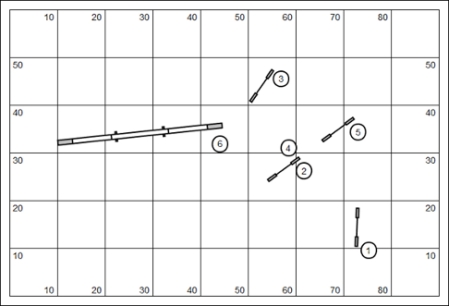

In this drawing a 10′ line and a 19′ line are shown. Obviously the 19′ line is the greater challenge. How does the line not remove movement… the most important directive or cue for the dog to continue on working?

I should love to leave that question just hanging out there. An answer would actually be better. Let me give two answers, actually:

- The handler’s movement should be calculated to arrive just short of the line at about the moment the dog is arriving at the objective obstacle.

- All skills are earned through training and practice. At the bottom of my blog in that little section “Questions comments & impassioned speeches” I routinely point to series of books I’ve written on distance training. If you need a series of exercises that lead to amazing distance skills… read and do the exercises in the 5 volumes of The Joker’s Notebook.

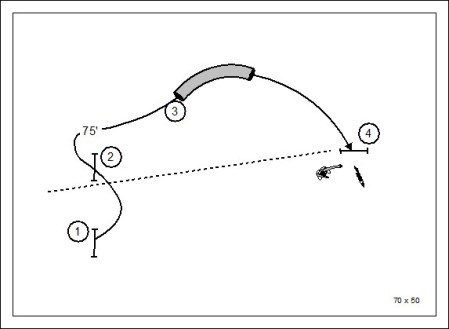

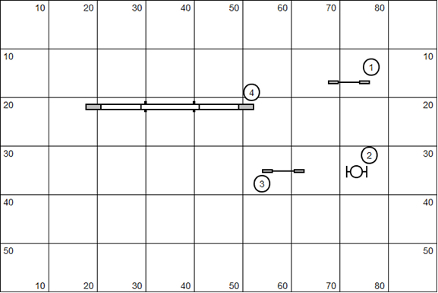

Parallel Path

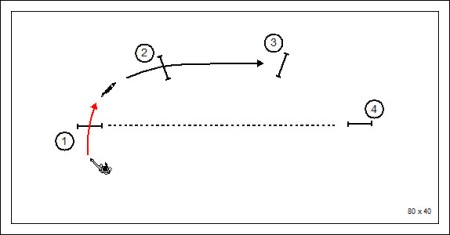

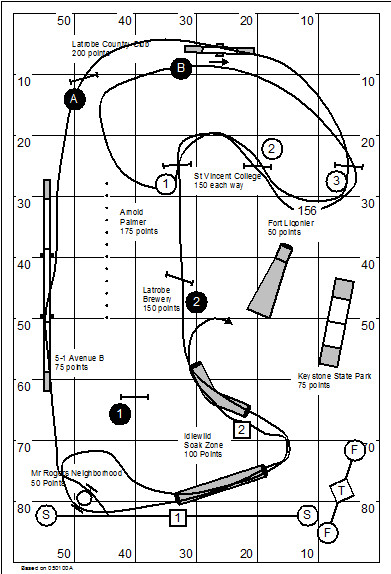

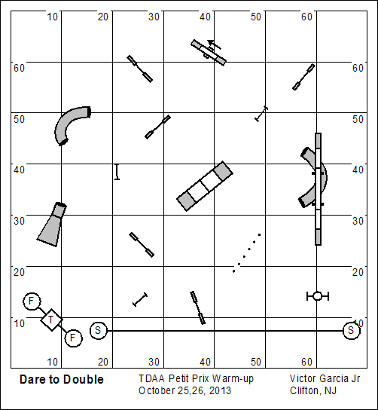

A typical kind of gamble that appears in distance classes of every sort is the parallel path. In this drawing, after the initial send, the dog and handler work for some distance in parallel. The course designer has to determine where the handler’s containment line should be, relative to the obstacles being performed at a lateral distance. Dogs at different levels might do the same series of obstacles, but at distances appropriate to the level of players.

Technical Obstacles

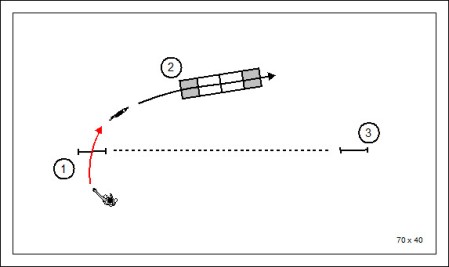

The parallel path gamble is made more challenging by the use of a technical obstacle (contacts and weaves) at the parallel distance. This is probably not an appropriate challenge for Novice/Games I players. But surely, Advanced/GII players can show off their training with this simple distance challenge.

One of the real complications in terms of the handler’s movement (required to direct the dog) is woven into the context of the handler’s application of that movement to assist the dog in the performance of the technical obstacle. Without careful training, the dog mightn’t understand the movement at any appreciable distance.

When a technical obstacle is used dogs should be judged by performance rules and faults appropriate to their level. In a numbered sequence the A-frame, in this example, is eligible to earn the dog a refusal fault, which would negate the gamble.

Discrimination

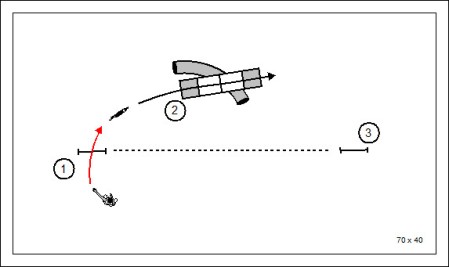

The course designer can raise the caliber of the challenge a bit by giving the dog a discrimination challenge in the performance of the technical obstacle at a lateral distance.

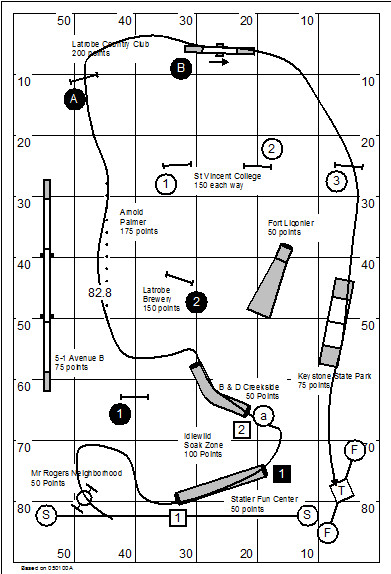

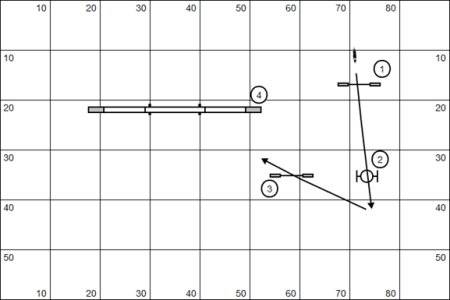

Change of Direction

This distance challenge begins with a “change of direction” challenge at an appreciable distance. This is a fairly tough kind of challenge, to be reserved for the Masters of our sport. Not only does the gamble feature a change of direction, but also a technical obstacle at a distance, and a discrimination challenge. It’s hard to get much more evil that this.

The Masters/GIII challenge doesn’t have to be anything more than a change of directions (at a distance), or a discrimination challenge (at a distance), or the performance of a technical obstacle (at a distance). The course designer really doesn’t have to do all three in one gamble!

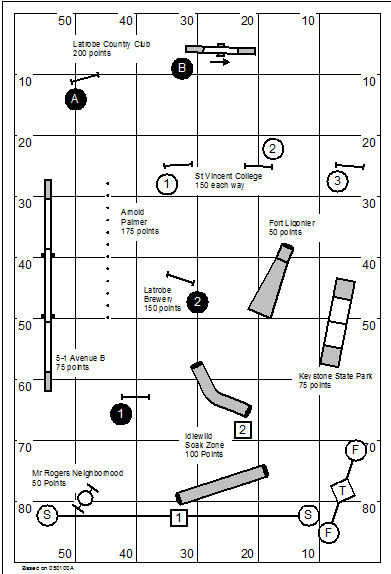

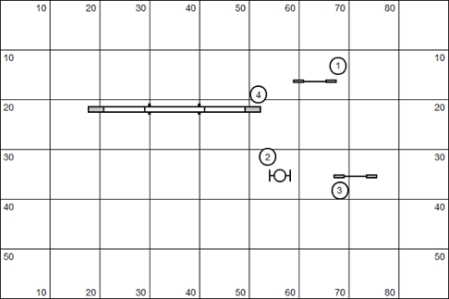

Establishing Gamble Time

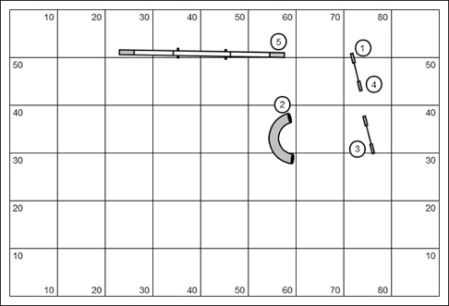

I’ve softened the previously drawn gamble challenge (considerably), mostly to talk about how times are assigned for performance of the gamble. In general the judge would take the wheeled distance of the dog’s path and then add 5 to 7 seconds to allow the handler to move the dog into position to begin the gamble.

Using this logic this gamble would be in the range of 13 to 15 seconds for dogs with 3 YPS (three yards per second) rate of travel. The course designer should acknowledge that turning the dog degrades the dog’s rate of travel. So we might add a second for the two turns that initiate the gamble.

Technical obstacles also degrade the dog’s rate of travel. So for each contact obstacle you might add 2 seconds. For the weave poles, add 3 seconds.

Designing for the TDAA

Please note that the sequences I’ve designed here are “big dog” distances. The distances between obstacles would be considerably tighter in the TDAA.

If there is an error that TDAA course designers make (too often)… it is in not giving adequate room to work. Interval distances might be opened up just a bit at a distance. But in general we subscribe to the same kind of spacing that we would use in any standard course. By definition:

- 8′ in the straightaway

- A minimum of 12′ to solve wrong course options, or on the approach to a technical challenge, or when requiring the dog to turn.

The TDAA course designer should also give the working dog credit for some distance working skill. I’ve reviewed courses in which the “distance challenge” was no more than 18”. That’s not really a distance challenge.

Yard Sale!

I’ve been loading thing up for a couple weeks now for a yard-sale at my in-laws place down in Williamstown, WV. Click HERE for details!

TDAA Judges’ Clinic and Trial in Lynwood, WA

Oct 9 – 10, 2014 TDAA Judge’s Clinic

Four Paw Sports Center, LLC

Lynnwood, WA

Clinic Presenter: Bud Houston

Contact: Robin Carlstrom robin@fourpawsports.com

Indoors on rubber matting over padding

Clinic Application

Oct 11 – 12, 2014 Trial T14005-9

Four Paw Sports Center, LLC

Lynnwood, WA

Judge of Record: Bud Houston (judging will be done by judge applicants, who may also enter the trial)

Contact: Robin Carlstrom robin@fourpawsports.com

Indoors on rubber matting over padding

Premium

Blog951

Questions comments & impassioned speeches to Bud Houston Houston.Bud@gmail.com. The web store is up and running. www.dogagility.org/newstore. I have five volumes (over 100 pp each) of The Joker’s Notebook available on my web-store at an inexpensive price. These are lesson plans suitable for individual or group classes for teaching dog to work at a distance.