One of the favorite games of the TDAA is Quidditch. It is a game of strategy, skill and daring. It is a game that owns a unique terminology and one that promises to make your brain explode as you work to understand the nuance of rules. Do you remember the first time you played Snooker? It’s kind of like that.

Quidditch begins the day on Sunday. It is fitting that this game of skill will be the game that decides what players will be set aside to finish the day to determine our national champions.

Quidditch

Hairy Pawter’s Quidditch is the invention of Becky Dean and Jean MacKenzie. The game was played for the first time at DogwoodTrainingCenter in Ostrander, Ohio.

Briefing

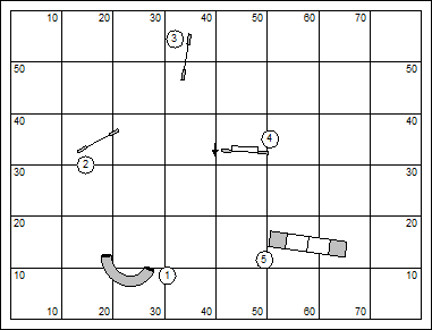

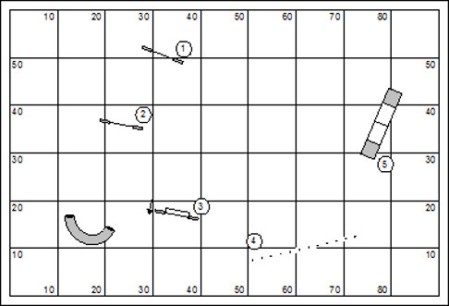

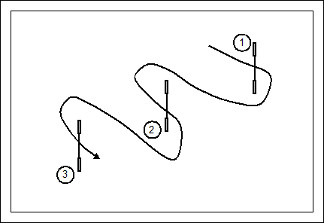

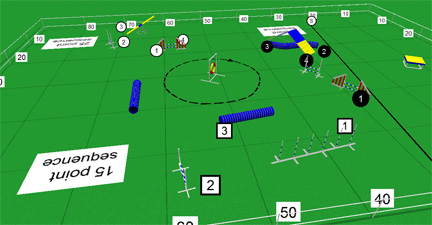

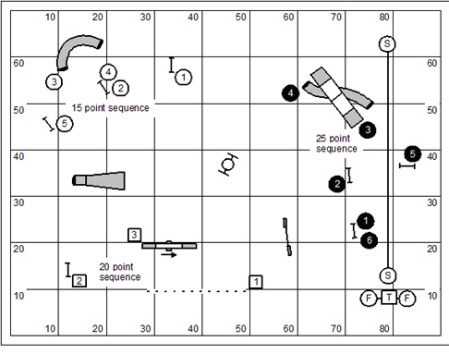

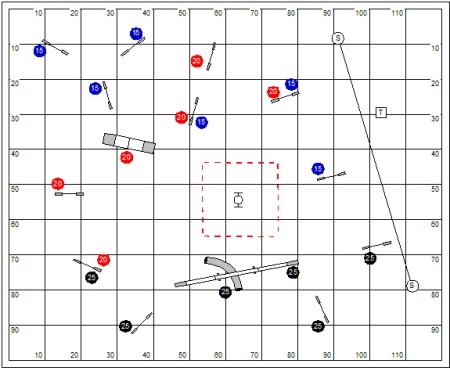

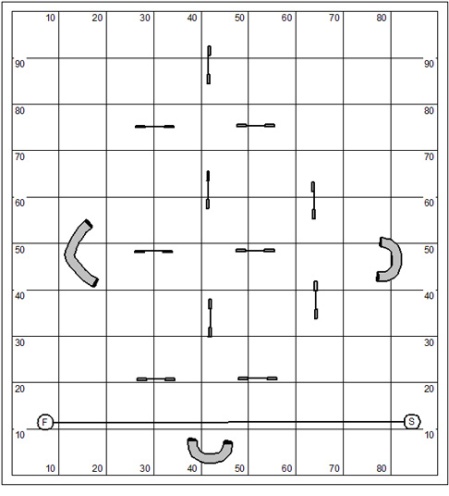

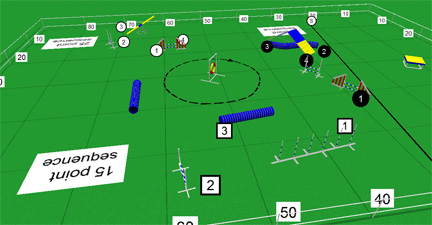

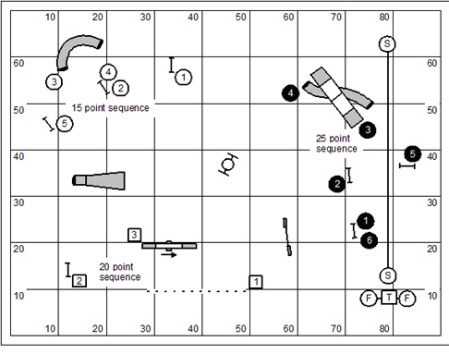

The objective of Quidditch is to perform three sequences and attempt to earn a bonus (the Beater) after each. The point values for each of the sequences are 15, 20, and 25 points respectively. Each sequence can be successfully completed only once. The sequences can be taken in any order.

The judge will assign Qualifying Course Time (QCT) respective to big dogs small dogs. All levels will compete with the same QCT (as each level has different qualifying points). When time expires the dog[1] should be directed to the table to stop time.

In case of a fault the team can immediately reattempt the same sequence or move to another sequence.

The three individual sequences can be successfully completed only once. Reattempting a sequence will not earn additional points.

When time expires no new points can be earned.

The Beater

Upon the successful completion of a sequence the team will have the opportunity to earn bonus points for a successful performance of a tire; the Beater bonus, for which the team will earn an additional 25 points.

At the option of the judge the attempt of the beater may require the handler to remain behind a containment line, making the beater a distance challenge.

Refusals will be faulted on the beater (the tire). The initial direction of the dog’s approach to the tire will define the run-out plane of the obstacle for the purpose of judging refusals. If a dog commits a refusal on the tire, the Beater bonus is lost.

After attempting the Beater bonus the team should attempt another three-obstacle sequence. Faulting the Beater does not fault the sequence prior to the attempt.

The Bludgers Rule

- A Bludger (wrong course obstacle) performed during the performance of an individual sequence shall result in a sequence fault. No points are earned for the performance of any individual obstacle unless the sequence is not completed due to expiration of time.

- Performance of a Bludger after the successful completion of a sequence on the way to the Beater (tire) shall be considered a fault of the Beater. The ability for the team to earn the Beater bonus is lost. The team should proceed to the next sequence, or to the table if appropriate.

- If the wrong course occurs: Bludgers (wrong courses) shall not be faulted: between the starting line and the first obstacle of a numbered sequence; between the Beater and the first obstacle of a numbered sequence; between the Beater and the table (to stop time).

- No points shall be earned for the performance of any Bludger.

The Keeper

If the team completes each of the different three-obstacle sequences, they will earn a ‘Keeper’ bonus of 50 points in addition to the points of the individual sequences. Note: the Keeper bonus is based on the three sequences alone and is not influenced by success on attempts to earn Beater bonuses.

The Golden Snitch

If a team successfully completes all three sequences, earns all three 25 point Beater bonuses, and touches the table prior to the expiration of time, the team will earn the Golden Snitch bonus of 75 points.

Scoring

Quidditch is scored points then time. The dog with the most points wins. In the case of a tie, the dog with the shortest time will be the winner.

A perfect score requires completion of all three sequences and successful performance of the Beater bonus. The scoring notation would look like this: 15-25-20-25-25-25-50-75.

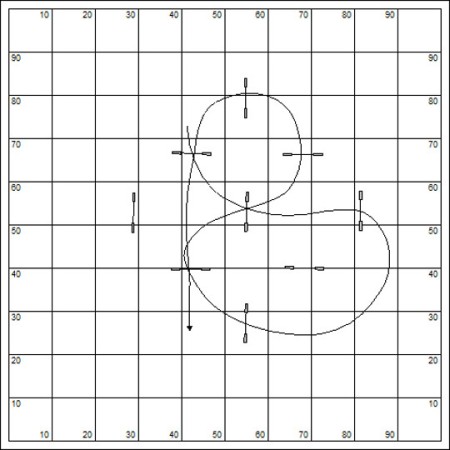

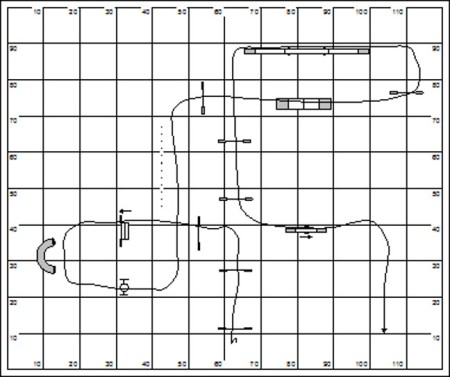

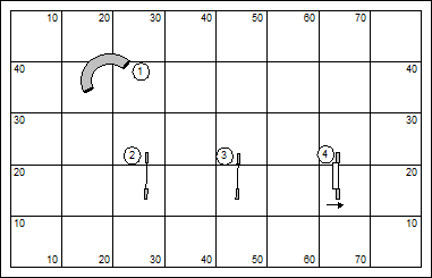

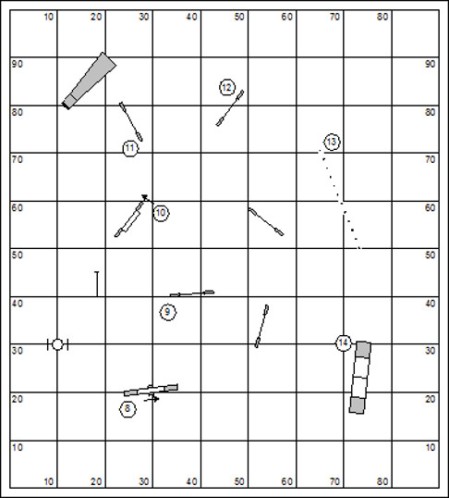

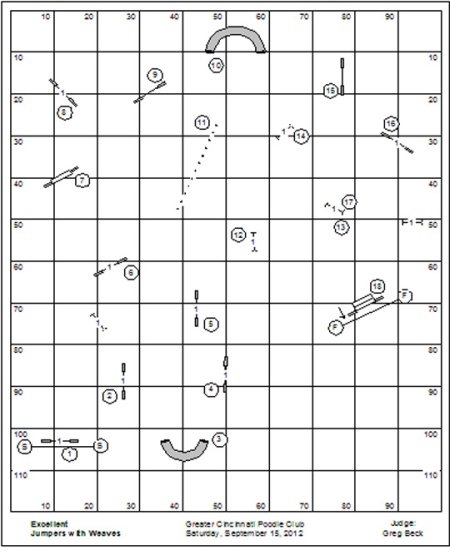

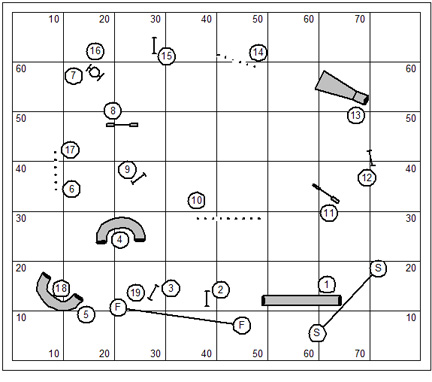

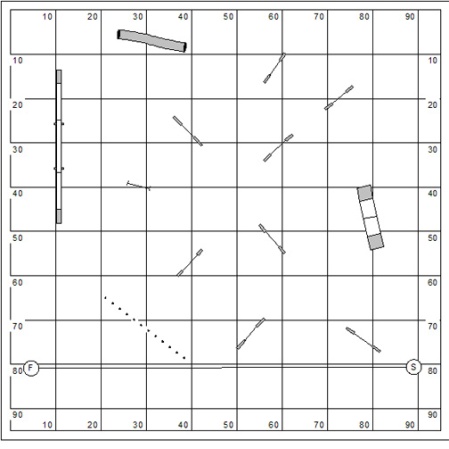

Course Design

With several years experience in designing and playing Quidditch (both in league play and in the TDAA) the game has evolved into a more interesting game of strategy and daring. In the early going each of the scoring sequences were typically limited to three obstacles only. This turns out to be not terribly interesting in terms of challenges.

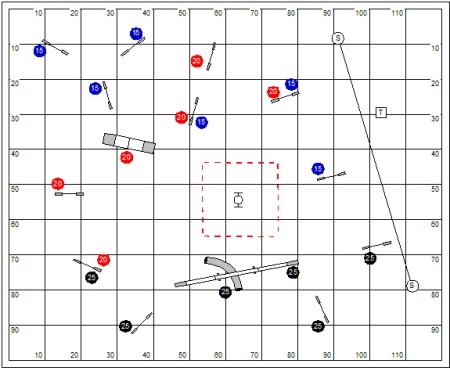

The judge/course designer should be aware that when the length of sequences are expanded the Qualifying Course Time (QCT) might have to be a bit longer. The rational system for applying QCT is to actually measure a modest strategy and then apply the rates of travel used in the standard classes, giving a small fudge factor for transitions between sequences.

Considerable thought should be given to the placement of Bludgers between the end of a scoring sequence and on the approach to the Beater. Sometimes the Bludger can be a simple ham-handed trap; and sometimes a subtle nuance of erstwhile scoring obstacles presented to entice the imagination of the dog.

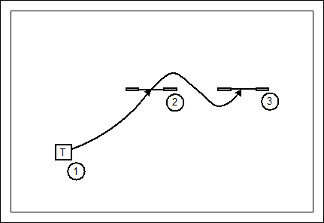

The Quidditch course is a matter of some simplicity. It requires three sequences that are arranged about the Beater. The Beater should be the tire.

Other obstacles that are not involved in scoring sequences are positioned about the course mostly to confound the team. These are Bludgers[2]. Often these Bludgers are positioned in that transition from a scoring sequence to the Beater. And so the dog’s path might take on a snookeresque quality and is the true test in the handler’s canny ability to manage the movement of his dog.

Use the same course for dogs competing at all levels. The level at which the dog qualifies depends upon the number of points earned.

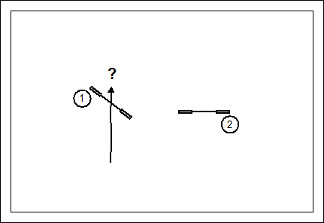

Send to Beater

Adding a bit more challenge to the Beater Bonus, in this variation the handler must send the dog to the Beater (the tire) from some distance. Therefore in the description of the Beater bonus the briefing should use this description:

Games II might also be required to send from a well-defined containment line; and possibly even Games I. However, Games I typically doesn’t need this complication.

Dealer’s Choice

The scoring sequences are unnumbered. The dog may be directed to do each of the obstacles in that sequence in any order. Note that a Bludger is not faulted between the Beater and any scoring sequence. Consequently, the handler may choose to direct his dog over an obstacle that is not a part of the intended scoring sequence before beginning it.

Judging Notes

Rules for performance respective to the dog’s level will be applied in judging the scoring sequences. That means (not to be exhaustive) the weave poles should be judged by level, and the contact obstacles by level.

Be aware that you will be judging the tire for refusals after the completion of a scoring sequence.

Understand how to judge Bludgers. A wrong course obstacle is only significant when the dog has freshly completed a scoring sequence and is approaching the Beater or, as in a standard course, taking a wrong course obstacle after beginning one of the scoring sequences. A skillful handler may direct his dog over obstacles for flow from the start line or after performance of a Beater.

Qualifying and Titles

Qualifying points required by level shall be:

- Games I: 110 points

- Games II: 135 points

- Games III: 160 points

Variations

* Houses of Hogwarts variation ~ In this variation there are four sequences, rather than only three. Typically on the course map the judge will assign both the name of the house and the value of the sequence: Gryffindor 25, Slytherin 25, Hufflepuff 20, and Ravenclaw 15.

* Original Rules ~ Some of the original rules of the game have been gently nudged aside to become more of a historical footnote and are not much observed these days. These are summarized below:

If a team completes or attempts one sequence more than once the final score for the team will be zero.

Each obstacle has individual point values that are earned by a team if a sequence is only partially completed prior to time expiring.

- 1 point for jumps

- 3 points for tunnels

- 5 points for contact obstacles and weave poles

The application of individual obstacle values can be ignored in routine competition in Quidditch. It really is not possible for the dog to qualify if all three sequences are not completed. However, in competitions like the TDAA’s Petit Prix this accounting method should be used because the last smattering of points earned will give additional differentiation for placement within the field.

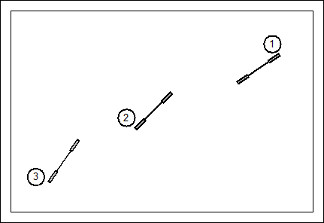

Competitors Analysis

Remember that Bludgers are significant only when you’re done with a scoring sequence and on the way to the Beater. Sometimes it might be desirable to take an obstacle for flow to move from one part of the field to another. Even if the dog offers performance of an obstacle when you’re making a transition across the field you should not waste time will silly call-offs. It’s better to take the flow and go.

The attempt of the Beater is a distance challenge. Give yourself room to move well. And, you don’t always have to look at it as a raw send (with your toes to the line, flapping your arms). It might be solved with you moving parallel to the dog, but at enough distance to stay on your side of the containment drawn by the judge.

Also, remember that the Beater is not tied to the scoring sequence. If your Beater fails… you need to go on to the next scoring sequence.

The game will be won, and possibly the Keeper bonus earned, if your strategy gives your dog the most efficient possible path. Beware of long unproductive transition between scoring opportunities.

Your analysis of the scoring sequences must include both the approach to the Beater (and awareness of Bludgers) and the flow from the Beater to the next scoring sequence, or to the table to end time. Make your dog’s movement as smooth and logical as possible.

Blog875

Questions comments & impassioned speeches to Bud Houston Houston.Bud@gmail.com. The web store is up and running. www.dogagility.org/newstore. I have five volumes (over 100 pp each) of The Joker’s Notebook available on my web-store at an inexpensive price. These are lesson plans suitable for individual or group classes for teaching dog to work at a distance.

[1] In this variation of the game the dog is naturally the Quaffle. But for the sake of clarity, we’ll just call him a dog.

[2] If we were to be true to the original game envisioned by J.K. Rowling, the Bludger would be a stick, and stewards might be assigned to whack the handler as he attempts to direct his dog to the Beater. At the end of the day, we decided to forgo this definition of the Bludger.